Dungeness in Kent, in the south of England, is recognised as Britain’s only desert (also as its largest shingle structure). It is the location of Prospect Cottage, where the artist, filmmaker and poet Derek Jarman spent his last years before his death in 1994. He had moved here from his long-term studio flat in Soho, above the Phoenix Theatre off Charing Cross Road, London. On first inspection, it is difficult to imagine two more different places in terms of colour and of mood (although perhaps reflection leads to a deeper level congruence).

Jeremy Reed, in referring back to Jarman’s Soho, asks the question ‘what colour is time when you try to remember it?’ (Reed 2014). He speaks of the ‘uncurtained window’ of Jarman’s tiny studio flat, ’like a grid framing the sky’. Answering his question, he tells us that he associates ’time with aqueous white rain skies over Leicester Square, and as candy-coloured stripes: pink and white, maroon and grey, pistachio and russet bands according to my abstract notation of big city seasons’ (Reed 2014).

Marc Almond, he of Soft Cell et al, and latter-day torch singer, lived less than a quarter of a mile away on Brewer Street at the heart of Soho’s lugubrious red-light district, in another studio flat overlooking the Raymond Revue Bar Theatre. Unsurprisingly, their paths would cross (somewhat frequently). This led Almond to suggest to Jarman that he shoot the low-budget video for his single, ‘Tenderness is a Weakness’. Jarman agreed, needing the finance for his bigger film projects as he was skint, and anyhow he liked to think of pop videos as a ‘cinema of small gestures’.

Fortunately, the revenue from Almond’s pop video (brilliant as it was), went on to subsidise larger film projects from ‘Planet Jarmania’, most notably the opulent Caravaggio from 1986. But it is the earlier 1970s films that drew me in. A Guardian Editorial this week tells us that ‘Cinema is in crisis, but Gen Z might save it from the streaming giants’ (Guardian 26.01.26). What a shame, when audiences have so little attention to give to cinema, too busy consuming and streaming pap. But the editorial also refers to the stirrings of a ’new kind of cine-love’ amongst Gen Z. Jarman’s cinema is well placed to induce this kind of resurrection, although be warned, this isn’t Netflix and chill! I have been interested in Jarman’s work since I first saw his 1978 film Jubilee, and then soon after his 1976 film Sebastiane (although I didn’t see them until well into the ’80s), respectively covering my twin obsessions of punk and Catholicism (more or less). As Tilda Swinton says, ‘you should have been a Catholic, Del’ (Swinton 2008). To make matters even more obsessive, he went and made a film about one of my favourite philosophers, Ludwig Wittgenstein.

Subsequently, I followed his corpus of painting, and then his writing (prose and poetry) and gardening, all connected to his political critique of the AIDS crisis, defence of Gay Liberation and his supremely brave testimony against homophobia. Diagnosed with HIV/AIDS in 1986, he was an early voice discussing the impact of AIDS and was notable for talking about his condition in public, both as an activist and as an artist.

Jarman always struck me as that rare kind of human being, honest (and genuinely courageous), as well as being terrifically iconoclastic and beautifully creative. In the last couple of years, I have visited his last place of existence, Dungeness, several times. Transfixed by its extraordinary vividness and desolate expanse in winter, by its more welcoming warm freedom in the summer. Visiting Jarman’s garden and home at Prospect House, I have also been drawn back to his writings and his art, which seem curiously prescient of our current times. This part of England has a long tradition of experimental writers. Nearby Rye was home to H.G. Wells and to Henry James, with the latter’s difficult prose seemingly connected to the hauntings of Lamb House. James finished his gothic novel The Turn of the Screw after moving into Lamb House, and claimed to have witnessed paranormal occurrences there. The ghost story writer E.F. Benson lived there after James. But Dungeness is haunted (and haunting) in a different, if related sense.

Figure 1. Prospect Cottage, Dungeness, Kent (December 2025).

The hauntology at the heart of this enigmatic desert space connects intrinsically to Jarman’s poetics and specifically his prose and poetry, which evolved somewhat later. He had started as a painter and an artist per se, studying Fine Art at the Slade School of Art. His film work followed and his poetry only seems to become a public expression closer to the time he moved to Dungeness. His absence is one of the paradigmatic missing links in Iain Sinclair’s anthology of British twentieth-century avant-garde poetics, Conductors of Chaos (Sinclair 1979). Jarman’s voice belongs naturally alongside this series of distinct and often conflictual voices and poetics, which were neglected within the more mainstream UK literary culture (I’d have his poems right up beside the aforementioned Jeremy Reed’s for example, another friend and comrade). Likewise, his aesthetic and political vision speaks more powerfully than any other to Sinclair’s incisive diagnosis of the malignancy of Thatcherism and even pre-Thatcher England, that ‘great rift between language and the material (political) environment, a specific collapse of our civic morality and ambition . . . the victim of rogue-capitalist relativism: nil by mouth indeed’ (Bond 2008). Plus ça change!

Tilda Swinton the actress, a close friend of Jarman’s, wrote a long letter to him after his death (‘Dear Derek’, ‘No Known Address’) (Swinton 2008). ‘Dear Derek, Jubilee is out on DVD. It’s as cheeky a bit of inspired old ham punk spunk nonsense as ever grew out of your brain and that’s saying something: what a buzz it gives me to look at it now’ (Swinton 2008: 10). In Figure 2’s film still, we see the graffiti of ‘Post Modern’ spraypainted across the main street wall. Jarman’s specific film, and his oeuvre more generally, can be seen as expressing a certain kind of postmodernism.

Figure 2. Still from Jubilee (Jarman 1978).

In Wake of the Imagination (Kearney 1998), Richard Kearney applies three different paradigms to the evolution of the artistic imagination over history. While the premodern period is distinguished by the paradigm of the ‘mirror’ (art as imitation or as ‘mimesis’), the modern period sees art develop around the more autonomous and creative paradigm of the ’lamp’, the artist and the artwork providing their own light on the world. Kearney reads the postmodern moment as marking a significant paradigm shift with the two previous epochs and is characterized by the paradigm of the ’lustre’. The lustre is a ‘chandelier with multiple glass pendants endlessly reflecting each other. There is no essential distinction between the image and thing, the empty signifier and the full signified, the imitator and the imitated’ (Kearney 1998: 288). As applied to arts and society, this leads to a fragmentation of perspectives and an undermining of unified meaning or understanding of art and or social values. Oftentimes, this postmodern moment is regarded negatively (as having a disorienting or vertiginous impact on creativity and agency).

However, an alternate and more affirmative possibility within this epoch for arts and society can be explored in this context as it evolves into a complex future, a conception of transformative aesthetics that I have recently defended in an extended essay (Irwin 2025). This reading of a postmodern affirmation originates in the poet and critic Charles Olson’s original coinage of the term as an open horizon of meaning and artistic practice (Olson 1960). Olson’s discussion of what he terms ‘Projective or Open or Field Verse’ (Olson 1960) points to more general possibilities associated with the postmodern moment across art forms. Olson calls the new verse ‘prospective, percussive, projectile [. . .] OPEN’ and distinctly different from what he associates with the ‘closed’ verse and aesthetics, even of late modernism (Olson 1960: 386). He refers to the ‘kinetics of the thing [. . .] a poem as energy transferred’, ‘form as an extension of content’, and ’the process of the poem [. . .] USE USE USE the process at all points, in any given poem always, always one perception must must must MOVE, INSTANTER, ON ANOTHER’ (Olson 1960: 388, original emphasis). Crucially, instead of this new postmodern movement in poetry constituting a return to either ‘objectivism’ or ‘subjectivism’ in art, Olson instead holds out for the renewal of the ‘relation between man and experience’ (Olson 1960: 395).

Olson’s concept of a multidisciplinary ‘Open Field’ can be seen as directly influential on Jarman’s vision of an interdisciplinary poetics and artistic practice, extending across painting, cinema, dance, poetry, prose and (even) gardening (as a more ’naturalised’ art form). The garden at Prospect Cottage is, after all, a work of art (amongst other things). The centrality of this concrete garden vision to Jarman’s life is strongly argued for (and poetised) in his posthumously published Pharmacopoeia: A Dungeness Notebook (Jarman 2022). It also can be traced in the inscription of John Donne’s poem across the side wall of the cottage, ‘The Sunne Rising’. ‘Love, all alike, no season knowes, nor clime / Nor houres, dayes, moneths, which are the rags of time’. Jarman, of course, despite all attempted appearances to the contrary, is a Romantic. It is just that his romanticism is often expressed in railing and flailing against the shallow materialisms of the age.

His film work, even as far back of the 1970s, was already consistent with this romantic strain as well as with the more methodological multidisciplinary Open Field approach. In an essay to commemorate 40 years of Jubilee as a film, ‘Grieve the Capital: Derek Jarman’s Jubilee Turns 40’ (Scovell 2018), Adam Scovell speaks to the prescience of the film with regard to British or even European contemporary consciousness. On first inspection, the film seems of a defiant mood with the Sex Pistols ‘God Save the Queen’ in Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee year of 1978 and as a kind of vulgarised provocation. For example, the Queen herself is mugged and killed for her crown early on in a Deptford edgeland.

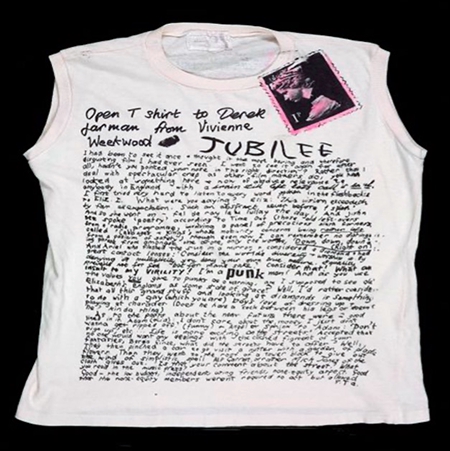

But there are other aspects to this cinematic text which are not so easily reducible. Vivienne Westwood’s infamous attack on Jarman in the form of an open letter on a t-shirt (Figure 3) indicates that his vision got under the skin of the punk rebels for being more satirical than celebratory. Westwood is unhappy with Jarman’s depiction of the commodification of the punk movement (at least in its early 1976 phase). Somewhat as a performative mea culpa, she printed the letter on a t-shirt and sold it in her and Malcolm McLaren’s shop, Sex (on the King’s Road) often associated with the Seditionaries label. ‘I had been to see it once (Jubilee) and thought it the most boring and disgusting film I have ever seen’.

Figure 3. Vivienne Westwood’s T-Shirt Open Letter to Derek Jarman (1978).

Jarman was, of course, wholly unapologetic: ‘The instigators of punk are the same old petit bourgeois art students, who a few months ago were David Bowie and Bryan Ferry look-alikes – who’ve read a little art history and adopted some Dadaist typography and bad manners, and who are now in the business of reproducing a fake street credibility’ (Jarman, quoted in Scovell, 2018). Was Derek right? Most probably, I’d say. Punk would have to wait to the second generation in the early ’80s (Crass, Conflict et al) to develop a more consistent and ethical approach to its inherent nihilism.

We conclude this essay with a couple of poems dedicated to Jarman’s vision of poetics, the kind of ‘brutal beauty’ as he called it instantiated at Prospect Cottage and more generally at the windswept Dungeness (especially in winter). As well as a more contemporary lyric of the kind of dystopia Jarman’s work often seemed to foretell (or as declared by The Sun this week, ‘Crash Burnham!’). This time as imagined in Keir Starmer’s Noir-esque dreamworks.

Jarman

Isn’t dead

He’s just waiting

For all the homophobes

To die slowly

Of something nasty

Jarman

Isn’t dead

He’s just waiting

In a Medieval bar

By an open fire

In Rye

For all the homophobes

To die slowly

Of something nasty

Dungeness Haiku

Hard sea blows bad

against black and

yellow wood

– stone heart

Keir Starmer Nightmare

Friday night British

Airways flight into London City

channels J.G. Ballard’s

darkest fantasies into reality

flying over Southend Pier where

my favourite Aunt Mona was from

all along the river Thames

with news that Orange Face

may want to take the UK

and do a deal with Farage

to enslave the non-white working classes

Figures

1.Prospect Cottage, Dungeness, Kent (December 2025).

2.Still from Jubilee (Jarman 1978).

3.Vivienne Westwood’s T-Shirt Open Letter to Derek Jarman (1978).

References

Creasy, Jonathan C. (Ed.) (2019) Black Mountain Poems. An Anthology. New Directions Press, New York.

Irwin, Jones (2025) ‘An Incredulity to Meta-narratives: Postmodern Philosophical Perspectives on Art and Education’ in Arts Education in Ireland: From Pedagogy to Practice. Edited by Dervil Jordan and Jane O’Hanlon. Intellect Books, Bristol.

Jarman, Derek (2008) Brutal Beauty. Serpentine Gallery. Book to accompany exhibition. Curated by Isaac Julien, London.

Jarman, Derek (2022) Pharmacopoeia. A Dungeness Notebook. Random House, London.

Jarman, Derek (2022) Through The Billboard Promised Land Without Ever Stopping. House Sparrow Press, London.

Jarman, Derek (2023) Blue. David Zwirner Books, New York.

Kearney, Richard (1998) The Wake of the Imagination. Manchester University Press, Manchester.

Olson, Charles (1960) ‘Projective verse’, in D. Allen (ed.), The New American Poetry 1945– 1960. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Reed, Jeremy (2014) ‘What Colour is Time? Derek Jarman’s Soho’ in ‘Jarman at 3am’. 3am Magazine, London.

Scovell, Adam (2018) ‘Grieve the Capital: Derek Jarman’s Jubilee Turns 40’. The Quietus, London.

Sinclair, Iain (Ed.) (1996) Conductors of Chaos. Poetry Anthology. Picador, London.

Swinton, Tilda (2008) ‘Dear Derek’ and ‘No Known Address’ in Jarman, Derek (2008) Brutal Beauty. Serpentine Gallery. Book to accompany exhibition. Curated by Isaac Julien, London.

Swinton, Tilda (2022) ‘Foreword’ to Jarman, Derek (2022) Pharmacopoeia. A Dungeness Notebook. Random House, London.