One year ago, in a previous Red Ogre Review essay of mine (‘A Poetic Psychogeography of London and Everywhere Now’), I started to explore London poetics, with reference to the evolution of the contemporary city (sometimes pernicious). I employed Iain Sinclair’s seminal anthology of British poetry, Conductors of Chaos (Sinclair 1996) to act as a touchstone for a discussion of the complex relations between writing and politics in specific authors. This essay continues this thematic, with a particular reference to the poetry of South London poet Katie Beswick, as contextualised by a wider discussion relating to psychogeography. There are many different angles on the complexity and vibrant life of London. Jonathan Jones recently described a comprehensive exhibition of East End artists Gilbert and George (‘21st Century Pictures’ at the Hayward Gallery) under the heading ‘a pulsating panorama of sex, violence and glorious urban grime’ (Jones 2025). Visiting this space, I was struck by the near-endless intersectionality of London as a metropolis. ‘All human existence is crystallised in their particular urban world, living and dying in their local streets. Yet the hardcore truth behind the hilarity is poetic. What stays with you is beauty’ (Jones 2025). Jones also notes that although the initial impact of this important retrospective is to disorient the viewer in a kind of ecstatic (pardon our French) ‘jouissance’, that there is underlying this ‘a stillness, a sadness and a romantic passion that breathes in this show’ (Jones 2025). A politics emerges from all this, although it is hardly linear or orthodox.

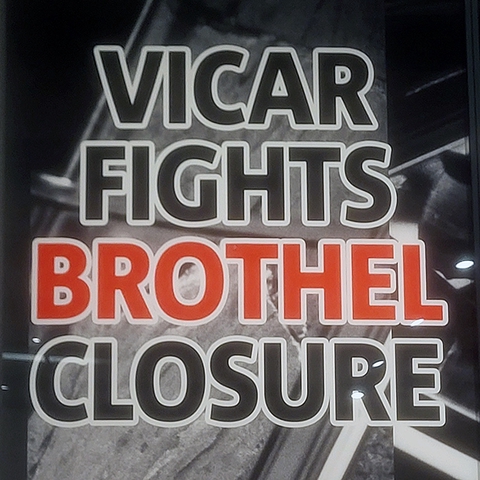

That said, the disorientation and derangement of the senses comes first. Ages (2001) is a yellow and red giant canvas with the artists’ faces admixed to a series of male sex worker adverts: ‘BLACK GUY, 24, Marco. Sexy horny and waiting’, ‘SKINHEAD JOE, 26, East End/10mins Liverpool St. Administers firm service’. Another canvas obsesses over Evening Standard billboards that keep shouting out about murder and every new depravity in the city. And yet in the midst of all of this madness, up steps a priest with his own perspective on what’s good and bad: ‘VICAR FIGHTS BROTHEL CLOSURE’. Well done, Revd Cecil, how open-minded of you!

Figure 1. From Gilbert and George, Hayward Gallery, South Bank, London (November 2025).

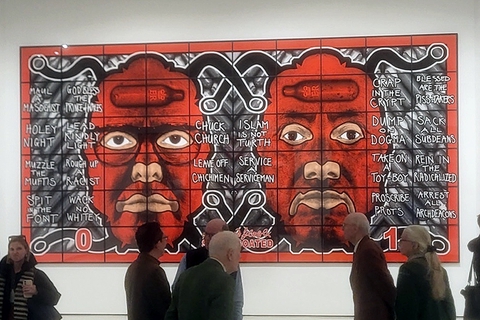

Another canvas admits their (and our) mutual obsessions: SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION. But also asks – WAS JESUS HETEROSEXUAL?, a painting that mixes the philosophical questioning with so many dizzying and colourful crucifixes. This retrospective combines their early work, produced in their fifties and sixties to work bang up to date now, in their eighties. Recent work seems more concerned with mortality and thanatology, there is a lot of cemetery depiction. But there is still joy to be had here in the face of finitude, Gibert and George wearing bright purple and green suits against the grey death stones. And lo and behold, there I was in early November, absorbing all this fascinating work, when I turn around in the gallery to see the two well-dressed chaps, looking at the very same canvas as me. There is indeed something wonderful about the way these artists mingle with their audience in a nonchalant but also caring manner (figure 2). If this is also a kind of London (even cosmic) psychogeography, then it is definitely a city space these artists inhabit themselves, as inscribed within, rather than standing outside as more abstract art may often want us to.

Figure 2. From Gilbert and George, Hayward Gallery, South Bank, London (November 2025).

Note the slangy and satirical phrases on the canvas. ‘Islam is not turth’[sic], ‘Dump on Dogma’, ‘Take on a Toyboy’ (Gilbert and George 2025). As said before, there is no (linear) politics here and religion and faith are especially a constant (and controversial, including disclaimers) target. ‘Chuck Church’! Another canvas here, ‘28 London Streets’, is a gallery of evocative street names from their East End neighbourhood. As Jonathan Jones notes, ‘in a way, lust for life is their religion. What are all these vast multi-coloured pictures if not stained-glass windows? Gilbert and George reverence nature, the city, their relationship’ (Jones 2025).

This everydayness and proximity of the art and artists, additionally a specific and implicit romanticism (however camouflaged), also brought me back to some of own personal experiences of London. Gigs at the Dublin Castle in Camden town, doing philosophy in Tottenham Hale, wild nights in Soho, watching Strictly in Welling, buying shellfish to cook at Borough Market, quaffing Albariño in Sidcup. A paradigmatic place for me has always been The Coach and Horses, a boozer with quite a decadent-artistic history. A short poem from my recent collection Deep Image pays personal homage to this infamous Greek Street interior and stimmung, channelling some of its (many) ghostly presences.

The Coach and Horses

I used to sit there up

at the barstool looking

at the photographs of

Jeffrey Bernard in mirror

reflection. Every so often

Francis Bacon would arrive

usually Tuesday evenings

which felt incongruous

as you’d be sitting there

with the 20th Century’s

greatest artist and literally

the place would be empty.

He would wax lyrical then silence.

Also, he’d been dead for years.

(Irwin 2025).

As well as the links to Bacon and Bernard, this poem also foregrounds a spectrality, a haunting mode of experiencing the city and its space, where time and memory blur and also hallucinate. In Iain Sinclair’s conceptual scheme, we are here entering the psychogeographic, that blending of situation and projection where truth or fact may be just one more (hardly even prioritised) aspect amongst other ciphers, to decode and interpret.

Sinclair’s anthology was groundbreaking in including versifiers such as Barry Mac Sweeney and Stewart Home, who in different and distinct ways, subverted the mainstream understanding of poetry and meaning (Sinclair 1996). The inclusion of Jeremy Reed is significant as Reed’s work connects poetry on the one side to music and song (as in his collaboration with Marc Almond on ‘Picadilly Bongo’ and on the biography Last Star) but also to British Surrealism (Sinclair 1996: 359). As well as including a selection of Reed’s own poetry, the volume allows poets to introduce the work of inspiring predecessors. Reed chooses David Gascoyne: ‘his extraordinary awareness of European poetry and his belief in imaginative vision . . . sets him apart from the prevailing British . . . social realism’ (Reed identifies the latter aesthetic ideology with Larkin and followers). Reed’s own poems carry this neo-surrealism onwards, grounded in London back alleys whilst calling to earlier seer poets that carried the flame: ‘And sometimes in the Soho streets/I anticipate meeting William Blake/leading two lions on leash down Wardour street’ (‘West End Dilemma’).

Sinclair’s poetry, collected in The Firewall (Sinclair 2006), is even more esoteric, but sometimes lands well in a related neo-surrealist key, with different undead spirits haunting this Londonese text: ‘Ronnie Kray is now in Broadmoor and brother Reggie in Parkhurst from where he is trying . . . to get a security firm called Budrill off the ground’ or ‘there’s a mob of rumours from s. of the river/challenging teak and shattering glass/with dropkicks honed on GLC grant aid’ (‘Autistic Poses’). South of the river might also recall a particular Burgessian nightmare vision, in A Clockwork Orange. ‘What’s it going to be then, eh? There was me, that is Alex, and my three droogs, that is Pete, Georgie and Dim, Dim being really dim, and we sat in the Korova Milkbar making up our rassoodocks what to do with the evening.’ (Burgess 2013: 7) And the following on Kubrick cinema scene, filmed from the infamous Thamesmead estate, with Alex and his droogs, and the gleeful evil, the pleasure in ‘a fair tap with a crowbar’, ‘we cracked into him lovely’, all in the search for a bit of the ‘auld Ultraviolence’ (Burgess 2013). By coincidence, Sinclair also writes the BFI introduction to J.G. Ballard’s Crash, which advocates ‘cine-films as group therapy’ and the making of amateur pornography skin-flicks (including advice on casting, narrative method and camera angles) in suburban bedrooms as an antidote to late capitalist ennui (Sinclair 1999). Wunderbar!

Speaking of ‘south of the river’, Katie Beswick’s recent chapbook Plumstead Pram Pushers (Beswick 2024) develops this kind of iconoclasm up to the present period, this time with a very distinct female voice and lens of experience. In her Foreword to the text, Beswick references her starting point as ‘adolescence . . . the sensations of a newly uncanny body’ (Beswick 2024: 6) but also that this development phase is ‘enduring’. Thus, it is not simply the original shock that the poet wishes to bear witness to but also how this problematic origin bequeaths a complex embodied legacy, ‘patterns of intimacy we form and eventually break or settle into’ (Beswick 2024: 6). Specific poems in the collection speak to both these aspects, the original opening of desire and its connection to the development of personhood and relationships. Tracing the evolution and genealogy of the work, Beswick foregrounds how the extended period of the writing (2014-2024) morphed from private writing into a ‘more coherent project exploring the contours of adolescence and desire’ as well as how this developmental process continues into adulthood and later relationships. As an abiding aspect of the meta-level work, the insult or slur of ‘slag’ is fore-fronted and interrogated.

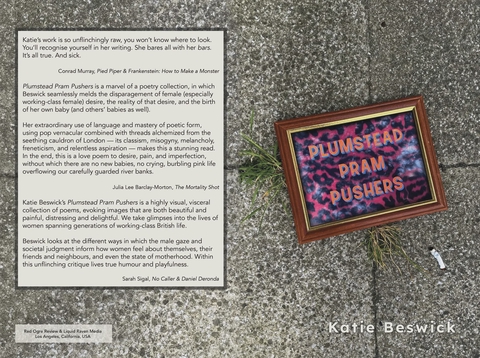

Figure 3. Cover art for Plumstead Pram Pushers, Katie Beswick (Red Ogre Review & Liquid Raven Media, 2024).

Plumstead Pram Pushers is a visceral book of poems, a kind of auto-fiction where autobiography and critical commentary on patriarchy and class inequality merge and complicate each other as the text progresses. ‘The slag holds fascinating contradictions – attraction and repulsion, excess and lack, shame and pleasure. She is in all of us, I think’ (Beswick 2024). This conceptualisation of a complicity or an implication of slagdom, across all genders and none, is important to remember in a world where it mostly gets applied to one grouping only (as Mark Stewart and The Pop Group had it, ‘we are all prostitutes’).

We see this phantasm or social construction (also very real in its effects of bullying and slandering, for example) of the ‘slag’ emerge in the first poem, ‘Sonnet for a Real Slag’, ‘Salt and vinegar Mc Coy’s for breakfast – pulls at your bedsheets like she’s hoisting masts’ (Beswick 2024: 8). And her (male) accomplice and counterpoint - ‘maybe you’re ready to fill up her, whole, with the shape of your love’. ‘Classy Birds’ and ‘Slaggy Manor’ complicate this initial scene with the picture of ‘teenage girls fucking . . . grown men’, with the on-line shows of the first poem (‘they kissed our virtual arses’) highlighting the oftentimes dangers of real exploitation and abuse, whilst more than not shrugged off with a ‘giggle’. The social class background and vulnerability of these poems runs throughout. In ‘A Rhyming Haiku About Class’, we have ‘working class don’t grass’. There is also significant pain witnessed in these poems. ‘Jackie Loses Her Virginity’ has the title character ‘withstanding the repulsion as he kissed her – the most swirling, spiky kiss ’ (next morning). And ‘Pike’ speaks to a more alienating experience of sex; ‘City cynical and hardened against caring . . . You acted so slaggy yesterday . . . Tells me he’s off don’t even say goodbye’. The ellipsis in the last line reads like a long and hurt silence and realisation of loss.

With ‘52A’, the ‘nights like bayonets/wisps of indiscriminate fucking’ are leading to nowhere very happy. As with the ‘Blues’, where ‘this is unhappiness/that I’m feeling’. The omens aren’t great, for sure. ‘From the Tarot deck/you pull the nine of swords’. In Tarot, this dreaded card’s appearance indicates a state of urgency, where the drawer of the card must face up to a state of inner torment (usually unacknowledged or in self- denial). However, the emergence of this sign in Tarot is also something potentially constructive, in being a call to confront these inner demons, rather than allowing them to silently overwhelm the stricken self.

This self-development of the character/s in the book begins to emerge in the middle to later poems. In ‘Sket’, ‘I’ll forgive you/but you weren’t on my side, damn!/ . . . Babe, you went too far – I click the phone shut. I’m not going back’. We can literally almost taste the feeling of individual freedom and liberation from a bad relationship. And in ‘Yattie’, ‘My mind is not in my thighs/My IQ’s higher’. With ‘Eating In’, we have the protagonist on better form, eating cold curry from the edge of the bed after satisfying sex, ‘stepped into dirty knickers/laughing and sated’. We might say this is a ‘both/and’ solution to romantic and erotic conundrums rather than an ‘either/or’. Also very funny, and this lightness of humour permeates the book, even in darker moments. In a similar key, we get a vivid deconstruction of that February 14th feeling. I’ll quote the full ‘A Thought on Valentine’s Day':

Remember that episode of EastEnders where Tanya buried Max alive in Epping Forest and then drove back and dug him up – monologuing a litany of his misdeeds as he choked on lumps of dirt and sobbed into soiled shirtsleeves?

I’ve been thinking about that today.

I don’t know why.

(Beswick 2024: 8).

The experience of childbirth and motherhood is also foregrounded in several poems in the book, with a different and very affirmative kind of tonality. In ‘Subchorionic Hematoma’ we have the midwifery nurse cast as a kind of magician; ‘The nurse moved the wand with precise turns . . . /She was no baby – she was a pulsing pearl . . . /She pulsed her pearly pulse and became my daughter’. This truly is a kind of magical transformation and extension of life and experience. In ‘Crevasse’, ‘at the cliff edge of motherhood’ and despite the unfortunate reappearance of the Tarot’s ‘nine of swords . . . bearing down their horizontal load’, instead emerges ‘life’s great surprise/out of you steps a person, naked and screaming’. If sex and desire sometimes bring us to close to death (literally and metaphorically) in Plumstead Pram Pushers, this stronger sense of bio-phily and love of life seems to win out. Despite the challenges, natality also signifies rebirth and renewal. With reference to the earlier discussion, the book is also striking in how it represents a combination of the traditions of social realism and (more or less) a kind of surrealist or more open-ended kind of poetics, also speaking to a newer and more personal kind of London psychogeography. This is a provocative, but also very rewarding and powerful, book to read and to engage with.

I conclude with some haikus of my own – London versions, as distinct from American haikus – with a taste of metropolitan dust and charm.

McPherson in London

Went to old mate Conor’s

play at Harold Pinter

– Irish ghost stories oooer!

Borough Market

Tuesday morning paella

With a surround of Japanese

Tourists – add octopus

Girl Crying on the DLR

Maybe the Ultraviolence

At Canning Town

Just gets her down

Poplar

Two Rastafarians

On the DLR Train

– Rhyming Linton

Kwesi Johnson

Housmans, Caledonian Road

No to gentri-catastrophe

Books have soul at

King’s Cross – not for sale

Figures

1.From Gilbert and George, Hayward Gallery, South Bank, London (November 2025).

2.From Gilbert and George, Hayward Gallery, South Bank, London (November 2025).

3.Cover art for Plumstead Pram Pushers, Katie Beswick (Red Ogre Review, 2024).

References

Beswick, Katie (2024) Plumstead Pram Pushers. Red Ogre Review, Los Angeles.

Beswick, Katie (2025) ‘Pushing the Boundaries On Hags, Slags, and Sluts: Poet Katie Beswick in Plumstead Pram Pushers’. Interviewed by Scott LaMascus in Lunch Ticket. Antioch University, Los Angeles.

Burgess, Anthony (2013) A Clockwork Orange. Penguin, London.

Gilbert and George (2025) 21st Century Pictures. Hayward Gallery, London.

Irwin, Jones (2025) Deep Image. Tofu Ink Press, San Francisco.

Jones, Jonathan (2025) ‘A Pulsating Panorama of Sex, Violence and Glorious Urban Grime’. Review of Gilbert and George (2025) 21st Century Pictures. The Guardian, London.

Sinclair, Iain (1996) Conductors of Chaos. Picador, London.

Sinclair, Iain (1999) Crash. David Cronenberg’s Post-Mortem on J.G. Ballard’s ‘Trajectory of Fate’. BFI Publishing, London.

Sinclair, Iain (2006) The Firewall: Selected Poems, 1979–2006. Etruscan Books, Wilkes-Barr.