The Madrid underground movement of the 1970s, known as ‘La Movida Madrileña’, was a vibrant countercultural movement that emerged in Madrid after Franco’s death in 1975. It is, of course, most famously associated with the initial works of perhaps Spain’s most famous cinema director, Pedro Almodóvar. But it also was the milieu for the development of a new poetry movement in the 1970s, entitled Novisimos (Newest Ones). This grouping took their name from an anthology Nueve novísimos poetas españoles (Nine Very New Spanish Poets), edited by the critic Josep Maria Castellet (Castellet 1970). The infamous Spanish poet Leopoldo Maria Panero began his writing with this tendency, alongside important fellow compatriots such as Montalbán and Gimferrer. Montalbán also wrote the hilarious (neo-Marxist) Pepe Carvalho detective novels and inspired the Sicilian detective hero in turn. Gimferrer is perhaps the closest Spanish poet in spirit to Panero, similarly unforgiving but revelatory, and both co-conspirators with the emerging punk movement in Madrid, Barcelona and beyond. Both poets imbibe the inspiration of popular culture in their poetics, for example in ‘First Poem’ (‘Primer Poema’ [Panero 2016]), where Panero cites Gimferrer citing Billie Holiday: ‘And truth, like death, is obscene/Strange fruit, said Gimferrer’ (Panero 2016). The reference is to the song (originally written in 1937 by Abel Meeropol) which captures the horror of brutal racist lynching-hangings of young black men in the deep American south. Despite the brutal show of sadism, the song manages to be melodious and subtle in response: ‘Southern trees bear a strange fruit / Blood on the leaves and blood at the root / Black bodies swinging in the Southern breeze / Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees’. This mode of cross-contamination of influences, a kind of bricolage, is characteristic of the Novisimos movement, as well as of ‘La Movida Madrileña’ (think of Almodovar’s second film, Pepi Luci Bom, for example [Almodovar 1980]). We might also see it as relating back to another brilliant Spaniard, Salvador Dali’s so-called ‘paranoiac-critical method’, in which ‘you hallucinate layers and metamorphoses of an object or image’ (Jones 2025). Dali’s painting and sculpture, as well as his cinema, often follow this dream logic (another inspiration for the Novisimos).

In broader literature terms, Panero is considered by many to be one of the most powerful poets of the last hundred years, albeit a troubled one. In May 2022, I published my first poem with Red Ogre Review, entitled ‘A Story About Panero #2’ (with an epigram from the poet, ‘only poetry can save us’), referring to the writer’s difficult relation to the psychiatric institutions of his home country:

How can a Madman write prose like this?

Panero’s existence itself is an Occultic Curse

And we are just puppets in his Universal Circus (Irwin 2022).

His life and writing maintain a somewhat mythic status in Latin American literature more generally. For example, the Chilean writer Roberto Bolaño has Panero appear as a slightly disguised character in several of his novels. In the novel 2666 (Bolaño year), ‘The Part about Amalfitano’ narrates the contagious influence of a disturbed Spanish poet. The reader is introduced to him via Professor Amalfitano’s recollection of his troubled marriage to his former wife, Lola, who left him on strange, ambiguous terms. ‘A genius, an alien… His legend and his poetry and the fervour of the true believer, a doglike fervour, the fervour of the whipped dog that’s spent the night or all its youth in the rain, Spain’s endless storm of dandruff, and has finally found a place to lay its head, no matter if it’s a bucket of putrid water’ (Bolaño 2008).

‘Madness is contagious,’ reflects Amalfitano. Here, Panero’s very real-life struggles with psychosis (originally institutionalised by his malevolent mother as a teenager, his whole life was characterised by experiences of psychiatric treatments and, oftentimes, maltreatment) become a symbol of a much more generalised predicament for social life; ’the Zoo that is Society’[‘del zoológico de la sociedad’] (Panero 2016). This social crisis, (or ‘madness’; ‘Psychiatric toxicologist/ask pain what my name is’ [Panero 2016]) is particularly associated for Panero with Spanish society since the 1930s, which connects his poetics strongly to the anti-fascist tendency in Spanish political life since the early twentieth century and through the Spanish Civil War and into Franco’s regime. Panero’s own father, also Leopoldo, was originally a famous and influential Leftist poet who became one of the establishment artists of the post-Republic Rightist regime, a volte-face betrayal which rankled with the son powerfully (and which was additionally never forgiven by the Spanish Left). As Andrew Faraday Giles has noted, ‘he [Panero] is also an important voice to help unravel Spain’s past and the pacto de silencio that hid the horrors of the Civil War until only recently. Panero does not give us answers to Spain’s predicament, but he does suggest new spaces to explore, dark spaces, nihilistic and irreal’ (Faraday Giles 2010).

Panero’s Novisimos movement fought against the Francoist regime vehemently (as did he personally, being jailed several times as a teenager for protest), leading in turn to the more buoyant and celebratory (queer) ‘La Movida Madrileña’. This movement, characterized by freedom, creativity, and hedonism, embraced new forms of music, fashion, art, and nightlife, challenging the established norms of the post-Franco era. But the seeds of this anti-Fascist cultural and poetic movement were sown several decades earlier, in the same late 1930s moments of despair that led Pablo Picasso to start on his epic Guernica canvas. Additionally, it can be argued that these connected approaches to politics and poetics have important resonances in the contemporary period of values crisis.

Picasso had until the later 1930s always considered art as separate from politics. But the murder of his good friend, Federico García Lorca, brought the realisation that art was inextricably connected to politics, whether we liked it or not, admitted it to ourselves or not. In July 2024, I visited a Picasso exhibition in Thessaloniki, Greece, entitled ‘Pablo Picasso: Exile and Nostalgia’. This exhibition was important for clarifying the emergence of Picasso’s political consciousness, as well as his writing of revealing prose poetry alongside his artistic works, carrying this political intent. Picasso’s prose poem ‘Dream and Lie of Franco’ (Picasso 2024; originally 1937) was included as an exhibit, a short text with images that prefigures the development of Guernica as a furiously anti-war and anti-Fascist giant canvas. The ‘Dream and Lie of Franco’ was intended to be sold as a series of postcards to raise funds for the Spanish Republican cause, the first known overtly Leftist statement from the artist towards his home country. The satirical imagery depicts Franco as jackbooted, carrying a sword and a flag. One scene depicts the dictator (to be) eating a dead horse. The work as a whole depicts the violent and gratuitous destruction of people, animals and possessions, shown to be in complete distress and disarray.

silver bells & cockle shells & guts braided in a row

a pinky in erection not a grape & not a fig.

casket on shoulders crammed with sausages & mouths

rage that contorts the drawing of a shadow that lashes teeth

nailed into sand the horse ripped open top to bottom in the sun.

cries of children cries of women cries of birds cries of flowers cries of wood and stone cries of bricks. (Picasso 1937/2024).

One of the striking aspects of Fascist ideology, which we see again in its more contemporary manifestations, is an anti-intellectual tendency. We might argue that Fascism isn’t really an ideology at all, it has no ideas base. This is captured in the Spanish Right declaration ‘Muerte la inteligensia’ or ‘death to intelligence’, infamously declared by Franco’s supporters at a rally at Salamanca in the 1930s. It is accompanied by an even more sinister principle of what can only be called (I borrow from Paulo Freire) ’necrophily’ or the ’love of death’ (Freire coins this term in his seminal text, Pedagogy of the Oppressed). At Salamanca, another refrain was ‘Viva la muerte!’ or ‘Long Live Death’. At this rally, the Leftist existential philosopher Miguel Unamuno was lucky to escape with his life. News of these developments reached Picasso, in political exile in France. But it was the subsequent murder of his friend in Andalusia, in his (beautiful) hometown of Granada, the great poet Lorca, which left him with no option in the art / politics debate.

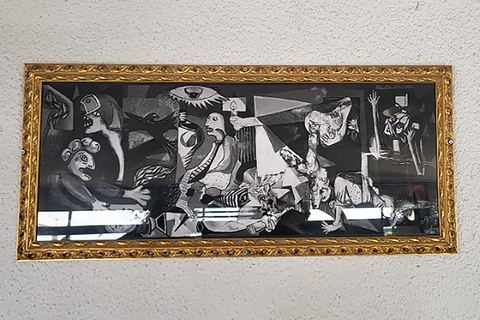

Contemporary resonances of this debate are all too clear. Across Europe and globally, we see the rise of Right Wing and Fascist politics. At times, the Left can seem paralysed to respond to these developments, or in other cases, the Left seems to compromise on its values in order to supposedly win the electorate back. In the last couple of years, I have spent some summers working in Greece, and have been struck by the emergence of a strong resistance to Right wing ideology (especially as expressed in the education system) through the Student Movement. In July 2024, I spent some time interviewing student leaders from different political groups across a range of Leftist ideologies. It was striking that Picasso’s vision of art and politics, and most paradigmatically his canvas of Guernica, struck a powerful contemporary chord for the student protestors. This resonance and cross-contamination of inspirations led the students to repaint Guernica, and the protest received official recognition from the University authorities (Aristotle University in Thessaloniki city), a painting now hanging in the Rectorate building of the institution (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Repainting of Picasso’s Guernica

I tried to capture some of this connected vision of politics in a series entitled ‘Student Revolt Thessaloniki Haikus’.1

Student Revolt Thessaloniki Haikus

I interviewed Alexis

Who told me about riots

– against the privatised University

At Aristotle Thessaloniki

Anarchists stage an occupation

– no to commercial education

Students repainted Guernica

To avoid the same fate

– it hangs in the Rectorate. (Irwin 2025).

The images of Guernica resonate through the years, acutely for us in times of war, because although the painting emerged out of an ethical disgust at a particular event, the bombing in April 1937 of an undefended Basque town during the Spanish Civil War by the German Luftwaffe, it contains nothing that refers directly to the place or the event (excepting its title). The figural elements extend beyond the specific horror of the bombing to a more generalised ethical horror at the all-too-real, all-too-painful consequences of war and terror violence, often on civilian and vulnerable populations. The symbolic motifs of the giant canvas continue to haunt us today in 2025; a tortured horse, a woman holding up a lamp, another woman weeping over a dead child. In particular, this last motif of a weeping mother came to obsess Picasso and at the Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid where Guernica is exhibited in its own room, you can also trace the various versions of the canvas, as well as the specific and obsessive drawings and re-drawings of each figure (the resonant photographs of Picasso’s painting process in his studio are captured by Dora Maar). The successive versions by Picasso of the weeping mother over her broken child are especially powerful and harrowing today.

In many ways, Leopoldo Maria Panero’s poetry, and that of the Novisimos, directly take up the challenge of Picasso’s work, avoiding literalist politics in favour of a poetic symbolism which seeks to regenerate Spanish culture and life from the necrophily which the Guernica canvas was an all-too-prescient warning of. Spanish culture and society with Franco and fascism was about to enter a phase of death (Picasso is here an ominous soothsayer) and it would be a long time coming through to the other side. Panero’s poetry foretells this last death knell of Spanish fascism, but perhaps also points ambiguously towards a liberatory escape (Georges Bataille being the thinker of the routes out of the infinite human labyrinth):

XI

And only darkness does not lie

So said Lord Bataille.

(Panero 2016).

The more liberatory escape had to await Franco’s natural death and in artistic terms, this leading in turn to the more buoyant and celebratory (queer) ‘La Movida Madrileña’. This movement, characterized by a specific hedonism, and headed up by the extraordinary figure (and cinema) of Almodovar, also recognised the residual ‘darkness’ that remained within the liberation. The insights of Picasso and Guernica from the 1930s remain perennial revelations, not to be neglected in the apparent glory of the new freedoms emergent. If the ‘dream and lie of Franco’ died a natural death in 1975, in 2025 it is more than evident that such fascist phantasms and fantasies are never far away from returning. Our students from Thessaloniki also show that new battles and struggles (political and poetic) continue to call on us, to respond ethically and with conscience and with human creativity. As Freire would say, let us continue to strongly counter necro-phily with bio-phily (’love of life’). La lutte continue. To conclude, I add some short poems to capture some of the complex inter-plays and inter-connections and cross-contaminations of this essay.

Dream and Lie of Franco, 1936 Haiku

Muerte la inteligensia! Viva la muerte! at Salamanca

Deep song of the duende

– Lorca is assassinated at Granada

Negistential Philosophy Haiku

God is dead

We are the killers

– playing nothing on punk guitar

Madrid Haiku

Paella at D’Stapa

After tomato anchoa

– discussing la Movida Madrileña

Footnote

1.Mignolo Arts / Pinky Thinker Press in New Jersey have developed an interdisciplinary translation of this haiku which also evinces a concern for borders and border-disciplinary crossings. Thanks to Mignolo, and especially to Charly Santagado, for their inspiring work on this. This work evinces a pluralist form of literature or a pluralist iteration of what Jacques Derrida called ’l’écriture’. For the Mignolo shared performance of the haiku, see here.

Figure

1.Repainting of Picasso’s Guernica by AntiCapitalist Students Thessaloniki, hanging in The Rectory, Aristotle Thessaloniki University, Greece (July 2024).

References

Almodóvar, Pedro (1980) Pepi, Luci, Bom y otras chicas del montón. Figaro Films, Madrid.

Attlee, James (2017) Guernica. Painting the End of the World. Head of Zeus, London.

Bolaño, Roberto (2008) 2666. A Novel. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York.

Castellet, Josep Maria (1970) Nueve novísimos poetas españoles (Nine Very New Spanish Poets). Ediciones Península, Barcelona.

Faraday Giles, Andrew (2010) ‘Leopoldo María Panero: POE-NERO (Gothic tyrant)’. NLP, Scotland.

Irwin, Jones (2022) ‘A Story of Panero #2’. Red Ogre Review, Los Angeles.

Irwin, Jones (2025) Deep Image. Tofu Ink Press, California.

Jones, Jonathan (2025) ‘Humble peasants . . . or an odyssey of sex and death?’. The Guardian, London.

Panero, Leopoldo Maria (2016) Rosa Enferma / The Sick Rose. Poems. Huerga and Fierro, Madrid.

Picasso, Pablo (2024) ‘Pablo Picasso: Exile and Nostalgia’. MOMus-Museum of Modern Art, Thessaloniki.